There are too many digital tools out there. It’s overwhelming.

When running Innovation Sprints or discussing with clients who want to accelerate their digital transformation, I often get asked which tools I recommend.

While it depends on what you want to test and your existing technical infrastructure, you still need a practical toolkit. Not a list of every fancy platform, just the ones that help you test ideas fast and learn what actually works.

Radio stations tend to spend months planning or simply rely on what I call the HiPPO (Highest-Paid Person’s Opinion) to make decisions, and often don’t test their assumptions.

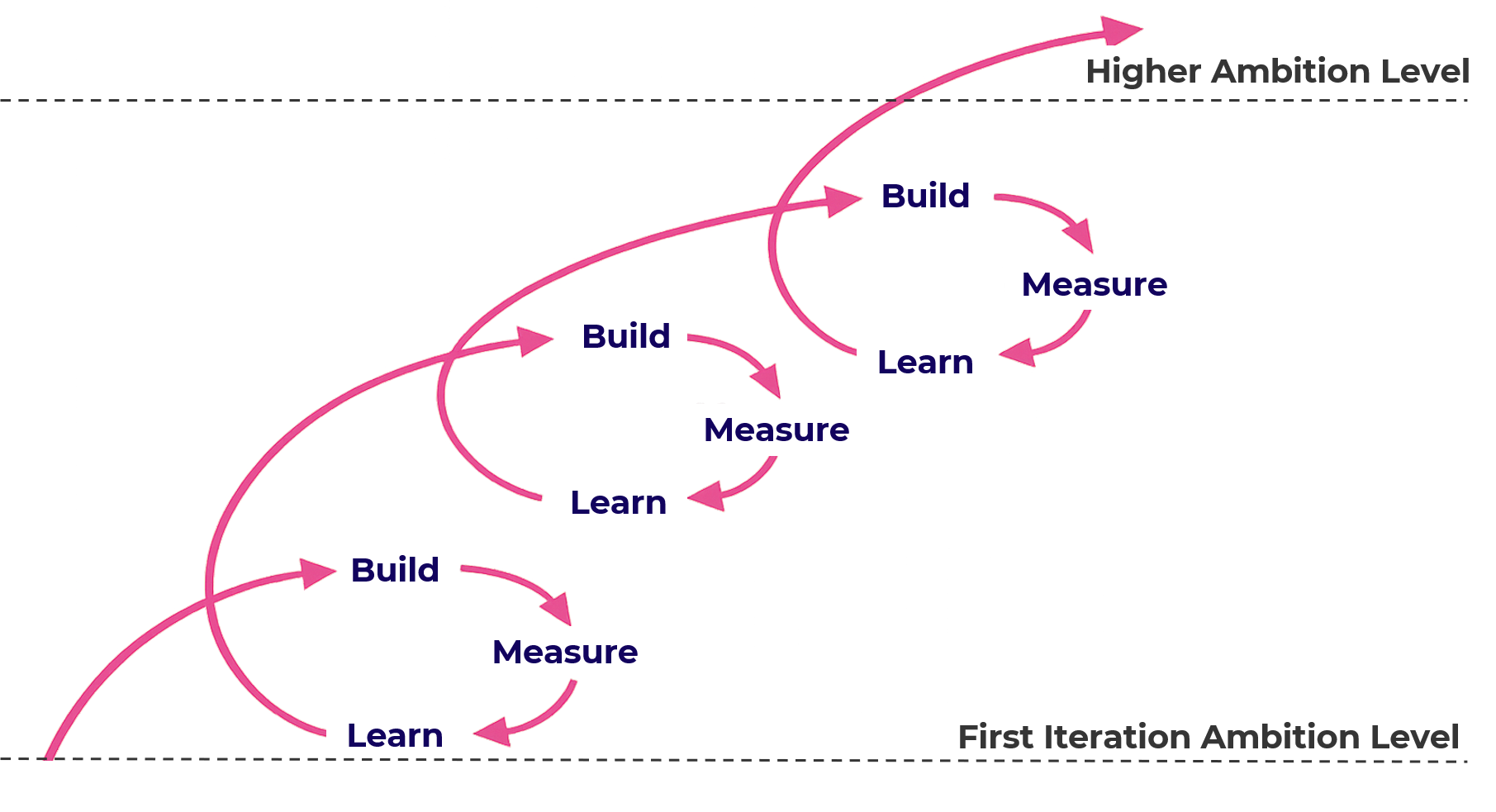

Startups, on the other hand, excel at testing. Structured experimentation is their superpower: they don’t plan their way to success, they test their way there. And that testing muscle is what radio stations need to build to succeed in their digital transformation.

A startup, for example, might spend €200 on ads to test whether anyone wants its new product before building it. Compare this to a radio station spending months developing a new show concept without ever validating if the audience cares. One approach learns fast. The other hopes for the best.

This guide covers 8 categories of tools that enable experimentation in radio. Most are free or cheap to start. All of them help you move from planning to testing and gain evidence that the idea is actually making sense.

The goal is to start learning, and these tools exist to help you test faster, fail cheaper, and find what actually works before committing real resources.

1. Landing Pages & Quick Tests

You want to launch a new podcast or show about a certain topic. Or a new service within your app. Before you commit weeks of production time, test if anyone actually wants it.

Landing pages let you describe the thing as if it exists and measure interest. Put up a “coming soon” page, drive some traffic, and see who signs up. If nobody cares, you just saved months of work.

Single-page websites you can build in 20 minutes. Good for “coming soon” pages or testing interest in a new show concept.

Landing page builder with A/B testing built in. Let’s you compare different versions to see which messaging works better.

More advanced landing pages with heatmaps and detailed analytics. Better if you need to convince stakeholders with data.

2. Interactive Prototypes

Your development team says the new app feature will take six weeks to build. Marketing wants to see it first. Your boss wants to approve it. Your audience has opinions you haven’t heard yet.

Prototypes solve this. They look and feel real enough to get honest reactions, but you can build them in days instead of months.

Click through screens. Test the flow. Show it to users. Watch where they get confused. All before writing a line of code.

The gap between what you imagine and what users understand is usually huge. Prototypes close that gap fast. You learn what works and what doesn’t while it’s still easy to change everything.

Design tool where you create clickable mockups of apps or websites. Your team can all work on the same file at once.

Type what you want in plain English, and it generates actual working website components. Feels weird at first but surprisingly useful.

Design tool that can publish real websites. The line between prototype and product gets blurry here.

Simple prototyping tool. Upload screens, connect them with clicks, and share the link. That’s it.

Build actual working web apps without code. Steeper learning curve, but you end up with something functional, not just a mockup.

3. Paid Traffic & Ads

Posting on social and hoping people find you doesn’t work anymore. You need to invest a small amount of money to drive traffic to your landing page and/or mockup. Want to know if 25-34-year-olds in Berlin care about a true crime podcast happening in the East German era? Spend €100 on Meta ads targeting that audience, send them to your landing page, and count the clicks. You’re buying data, not customers.

Target very specific demographics. Good for testing whether your content idea resonates with the audience you think wants it.

Catch people who are already searching for topics related to your content. Useful for validating demand.

Younger audience. Video-first. Expensive to learn, but worth it if that’s where your future listeners are.

Reach people while they’re already listening to audio. Probably the best for testing audio content concepts.

4. Video & Audio Content Creation

Radio people know audio. But testing digital content means you also need video for social platforms, clips for TikTok, and audiograms for Instagram.

Waiting for your production team probably means you don’t test much. These tools let you create decent content yourself, fast enough for experimentation to be feasible. You don’t need broadcast quality for a test. You need “good enough to learn from” quality.

Free video editing app. Has templates optimized for TikTok and Instagram Reels. Good enough for most social content.

Edit audio or video by editing the transcript. Remove filler words automatically. Also does AI voices if you need to fix mistakes.

Record remote interviews that sound like everyone’s in the same studio. Each person’s audio is recorded locally on their device.

Upload your raw audio, it fixes the levels and removes noise automatically. No manual post-production needed.

5. Content Distribution

You created a great episode or show prototype. Now it needs to reach people. Either test it privately with a select group using a webplayer, or distribute it publicly across Apple Podcasts, Spotify, YouTube, your website, Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok.

Doing this manually means you’ll publish less and test less. Distribution tools automate the boring parts. The easier it is to distribute content, the more experiments you can run.

European podcast hosting that distributes to Apple, Spotify, and everywhere else automatically. You can also use their webplayer, so that the content is visible only to a selected audience. Analytics included.

Advanced podcast US-based hosting with dynamic ad insertion. For when you’re ready to monetize.

Schedule posts across Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn from one place. Set it and forget it.

Social media scheduler built for visual platforms. Good Instagram and TikTok planning features.

6. Analytics & Behavior Tracking

Everyone has opinions about what works. A program director thinks one thing. A marketing executive thinks another. And the ad sales team has its own theory.

Behavior data ends the arguments. Did they click play? How long did they listen? Did they come back? Traditional radio metrics measure exposure/reach. Digital analytics tell you about engagement and retention.

Free website and app analytics. Shows where visitors come from and what they do on your site. Industry standard.

Privacy-focused analytics. You host the data yourself. Good alternative if GDPR compliance matters.

Track specific actions people take. “Did they click play?” “Did they finish the episode?” Answers behavioral questions, not just traffic counts.

Similar to Mixpanel but better for tracking user journeys over time. See patterns in how people engage.

Shows exactly how people interact with your site through heatmaps and session replays. Expensive but comprehensive.

7. Audience Research

Analytics tell you what people do. Audience research tells you why.

You see people drop off after 15 minutes. But you don’t know if it’s because the content gets boring or they’ve just arrived at work. So you ask them. The best decisions combine behavior data with direct conversations.

EU-based free forms that look good and work well. No branding, logic jumps, and file uploads. Easier than it sounds.

Everyone knows it. It’s free and works with Google Sheets. Sometimes boring is fine.

Like Google Forms, but integrates with Microsoft 365. Use it if your station already lives in that ecosystem.

Forms that feel like conversations. People finish them more often. Costs money, but worth it for important surveys.

8. Content Research & AI Tools

You need to research competitors, analyze transcripts, or pull insights from listener interviews. Doing this manually takes days. AI tools do it in minutes.

They don’t replace your judgment. They accelerate your research. Upload a transcript and ask questions. Research a topic with cited sources. The value is exploring more possibilities faster.

AI search that gives you answers with sources. Good for quick research on topics you don’t know well.

AI that handles long documents and detailed analysis. Upload transcripts or research papers and ask questions about them.

Upload your own documents and have AI-powered conversations about them. Helps you find patterns in your own content.

What To Do With This List

Don’t try to use all of these, that’s not the point. Pick one category where you’re stuck. Try one tool. Run one small experiment. Learn something specific.

The tools don’t matter as much as the habit of testing instead of planning.

Most radio innovation fails not because of bad tools but because teams never move from a hope or a strategy presentation to actual experiments. These tools help you test faster and learn more cost-effectively.

That’s it. Now you have no excuses not to start testing.