La radio ne souffre pas d’un manque d’idées. La plupart des organisations avec lesquelles je travaille en regorgent.

Les équipes ont des opinions sur les formats, les plateformes, les workflows, les outils, la gouvernance et les métriques. Il y a des slides qui expliquent où l’industrie se dirige et pourquoi l’action est urgente. Les diagnostics ne manquent pas.

Et pourtant, quand on prend du recul, les progrès semblent souvent étrangement prudents.

Non pas parce que la radio ne comprend pas ce qui se passe (la bascule vers le numérique et la consommation à la demande s’accélère), mais parce que de nombreuses organisations hésitent au moment précis où les hypothèses rencontrent la réalité, là où on arrête de débattre et où on commence à mesurer.

Cette hésitation a un nom : FOFO, pour Fear Of Finding Out (la peur de découvrir).

Cela n’a pas grand-chose à voir avec la technologie, les budgets ou même les compétences. FOFO est psychologique. Et en 2026, c’est peut-être l’une des principales raisons pour lesquelles la transformation numérique continue de stagner.

À quoi ressemble FOFO dans la radio

FOFO est rarement explicite. Personne ne dit « N’allons pas regarder les données ». Cela se cache en fait derrière des comportements parfaitement raisonnables.

Il y a une préférence pour la planification plutôt que pour les tests. J’ai un jour été dans une salle où une équipe a passé une demi-heure à débattre de la feuille de route future d’un podcast, et – avant que j’intervienne – pas une minute à regarder le taux de complétion du contenu existant et la rétention pour voir si les auditeurs aimaient réellement les premiers épisodes.

Planifier est confortable. Regarder les données brutes pourrait être inconfortable.

Cela se manifeste aussi dans les métriques que les organisations choisissent de mettre en avant. La portée de la radio linéaire est confortable. Les chiffres de téléchargements sont rassurants. Ils créent l’impression d’échelle et de momentum.

Mais qu’en est-il de la baisse du temps d’écoute ? Qu’en est-il des écoutes réelles et de la complétion plutôt que des simples téléchargements (un téléchargement n’est pas une écoute) ?

Les métriques liées au comportement – complétion, rétention, fréquence – bien qu’essentielles, sont clairement moins populaires. Elles soulèvent des questions. Et dans de nombreux marchés, les systèmes de mesure eux-mêmes rendent encore ces questions faciles à éviter.

FOFO n’est pas un problème interne. C’est toute l’industrie qui est concernée, renforcée par la manière dont la radio est mesurée.

Prenez la mesure d’audience. Les recherches d’EGTA montrent un schéma cohérent dans les marchés qui passent d’enquêtes déclaratives à une mesure passive ou hybride. La portée a tendance à rester plus ou moins stable, mais le temps d’écoute, lui, chute brutalement, souvent dans une fourchette de 20 à 30 %.

Non pas parce que les audiences changent soudainement de comportement, mais parce que la mesure passive élimine le biais de mémoire et capture ce que les gens font réellement, et non ce qu’ils croient faire.

Cette chute est inconfortable. Elle affecte l’inventaire, la tarification et les hypothèses sur la performance de la radio.

Dans le même temps, la direction est claire : les annonceurs et les agences attendent de plus en plus de données comportementales, en temps quasi réel, comparables au numérique et au streaming vidéo. Pas simplement des chiffres déclaratifs gonflés.

FOFO est également présent lorsque des initiatives numériques sont étiquetées comme « expérimentations » mais ne sont jamais conçues pour véritablement remettre en question les hypothèses. L’objectif se déplace discrètement : de l’apprentissage de quelque chose de nouveau vers la confirmation de quelque chose de familier.

Les organisations radio n’évitent pas ces moments par paresse. Elles les évitent parce qu’elles tiennent à leur sujet. À leur marque. À leurs succès passés. À ne pas être la personne qui doit dire : « Ça ne marche pas comme on l’espérait. »

Pourquoi FOFO est devenu un vrai problème

En refusant de regarder, on refuse d’agir.

FOFO fonctionne comme le fait d’éviter un rendez-vous chez le médecin. Non pas parce qu’on se sent bien, mais parce qu’on a peur de ce qu’on pourrait entendre. Le problème ne disparaît pas. Il reste non traité. Et plus on attend, moins il reste d’options.

La même dynamique s’applique ici. Tant que les données inconfortables ne sont pas examinées, les problèmes sous-jacents ne sont pas traités. Les formats ne sont pas ajustés. Les choix de distribution ne sont pas remis en question. Les décisions d’investissement restent théoriques.

Le danger, c’est que FOFO n’apparaît rarement immédiatement dans les chiffres.

Au début, tout semble aller bien. Les équipes restent actives et occupées, exécutent des plans et affinent des narratifs, tout en s’éloignant progressivement du comportement réel de l’audience. Les métriques qui confirment ce qui « sonne bien » sont amplifiées ; les signaux qui le remettent en question sont reportés ou ignorés. De bons indicateurs sont les communiqués de presse des stations à la suite des résultats d’une vague de mesures.

Cela crée une fausse réassurance. La stabilité devient une histoire que les organisations se racontent, mais à un moment donné, elle cessera d’être crédible.

Et au moment où la pression force les décisions, l’éventail des options a disparu. Les petites expérimentations peu coûteuses qui auraient pu éclairer le chemin à suivre ne sont plus possibles. Ce qui aurait pu être testé légèrement nécessite désormais une restructuration, une consolidation ou des mouvements défensifs.

FOFO n’empêche pas les mauvaises nouvelles. Il les reporte simplement, tout en rendant la réponse plus lente, plus risquée et plus coûteuse.

Comment briser FOFO

Briser FOFO commence par une étape simple et inconfortable : accepter de regarder.

Pas tout. Pas le tableau de bord parfait qui n’existe pas. Mais les points de données dont on sait déjà qu’ils sont gênants. Ceux qui arrivent rarement dans les présentations. Les taux de complétion des émissions, la fréquence d’utilisation de votre application, le taux de rétention des nouveaux auditeurs, les moments d’abandon… les chiffres qui remettent discrètement en question le narratif.

Tant que ceux-ci ne sont pas reconnus, rien d’autre ne bouge vraiment. Non pas parce que les équipes sont incapables, mais parce qu’on ne peut pas réparer ce qu’on refuse de nommer.

La deuxième étape consiste à accepter quelque chose avec lequel la radio a historiquement eu du mal : vous ne savez pas encore ce que vous ne savez pas.

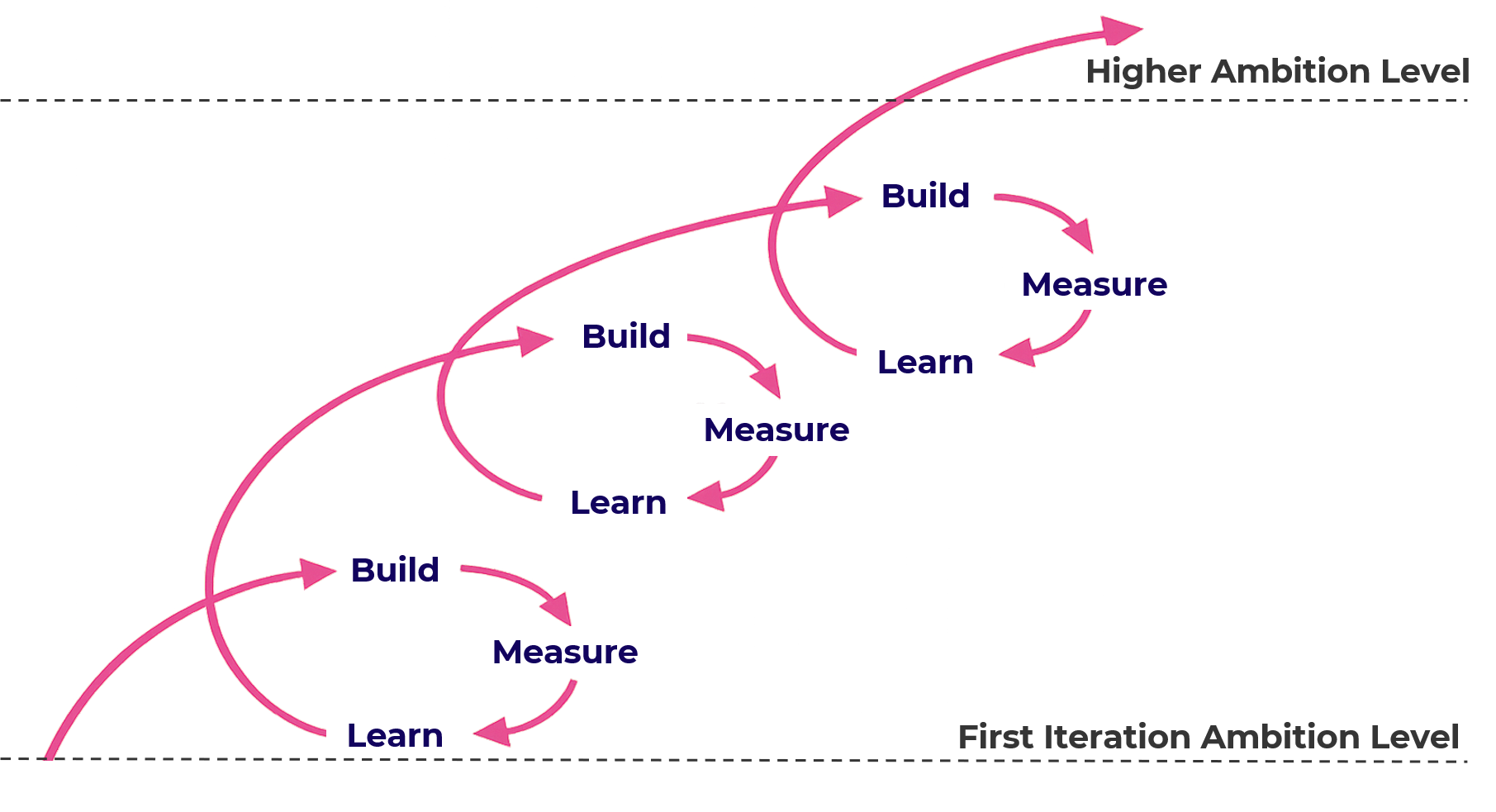

C’est là que l’expérimentation compte. Pas comme un mot à la mode, et pas comme du théâtre d’innovation, mais comme un moyen de remplacer les opinions par des preuves. Beaucoup des échecs que je décris dans mes articles précédents et dans mon livre, des podcasts surproduits qui ne trouvent jamais leur public aux extensions numériques qui semblent bien sur le papier mais restent inutilisées, partagent la même cause profonde : les hypothèses n’ont jamais été testées. Par peur de découvrir.

La radio a passé des décennies à optimiser des variables connues comme les grilles ou les formats. Mais le numérique ne récompense pas l’optimisation du connu. Il récompense la découverte de l’inconnu.

Cette découverte ne nécessite ni grands lancements ni paris risqués. Elle nécessite de petites expérimentations délibérées conçues pour répondre à des questions spécifiques : Mes efforts pour promouvoir du contenu sur TikTok ramènent-ils réellement des auditeurs, et reviennent-ils ? Vaut-il mieux publier deux épisodes de 10 minutes ou un seul de 20 minutes ?

Les expérimentations ne visent pas à avoir raison. Elles visent à découvrir.

Une fois que les organisations acceptent que l’apprentissage précède la confiance, et non l’inverse, FOFO commence à perdre son emprise. Les décisions deviennent plus faciles. Les arbitrages deviennent plus clairs. Et le progrès cesse de ressembler à un saut dans le vide.

FOFO est un choix

À un moment donné, chaque organisation fait face à la même décision.

Vous pouvez préserver le confort maintenant et gérer les conséquences plus tard. Ou accepter l’inconfort tôt, tant qu’il reste encore de la marge pour ajuster.

La transformation numérique ne récompense pas la confiance. Elle récompense l’honnêteté. La volonté de regarder les choses telles qu’elles sont, et non telles que nous voudrions qu’elles soient.

FOFO est humain. C’est compréhensible. Mais c’est aussi un choix.

Et en 2026, c’est un choix coûteux.